Parashat Korach begins not with laws or instructions, but with conflict. Not the quiet disagreements that simmer under the surface of communities—but full-blown rebellion. Korach, along with 250 chieftains, confronts Moses and Aaron with a cry that sounds, at first, like a protest for justice:

"Rav lachem! You have gone too far. All the community are holy, every one of them, and the Lord is in their midst. Why then do you raise yourselves above the congregation of the Lord?" (Numbers 16:3)

This verse has echoed through generations as a rallying cry for populist revolt. Korach appears to argue on behalf of equality, dignity, and shared holiness. His words echo God’s own declaration at Sinai: “You shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). But despite the persuasive rhetoric, the Torah responds with swift and violent judgment. The earth itself opens to swallow the rebels.

Why such a harsh punishment for what seems like a theological dispute?

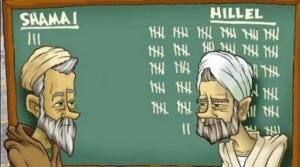

Pirkei Avot 5:17 offers a crucial lens:

"Any argument that is for the sake of Heaven will endure, but one that is not for the sake of Heaven will not endure. What is an example of an argument for the sake of Heaven? The disputes between Hillel and Shammai. And what is an example of one not for the sake of Heaven? The dispute of Korach and his company."

This Mishnah makes a subtle but powerful claim: disagreement itself is not the problem. On the contrary, machloket—dispute—is fundamental to Torah. The Talmud is built on disagreement. The Midrash multiplies meanings. Even our liturgy preserves debates (e.g. the differing versions of the Shema and Amidah). Judaism, more than any other tradition, treats debate as sacred. But not all arguments are holy. There are rules, ethics, and intentions that determine whether a disagreement builds the world—or tears it apart.

The classic example of a sacred disagreement is that of Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. In Eruvin 13b, the Talmud recounts a heavenly voice that declared:

"These and those are the words of the living God, but the law is in accordance with Beit Hillel." Why? Because Beit Hillel were “modest and patient, and they would teach both their own views and the views of Beit Shammai—and would even prioritize the views of Beit Shammai before their own.”

Here is the first ethical marker of sacred argument: epistemic humility. The willingness to articulate the other side’s position as generously as your own. To argue not to vanquish, but to understand. The Talmud is filled with this spirit—rabbis preserving dissenting views across centuries, even when those views are not halakhically adopted. Why? Because preserving the voice of the other is itself a religious act.

Korach fails this test. His claim may sound egalitarian, but as Midrash Tanchuma (Korach 1) notes, it emerges from jealousy. Korach was passed over for a leadership role, and his rebellion is a veiled power grab. The Zohar adds a mystical dimension, describing Korach as seeking kavod, not kodesh—honor, not holiness. His protest is not l’shem shamayim (for the sake of Heaven), but l’shem atzmo—for the sake of himself.

This leads to the second test of sacred disagreement: motive. Why am I entering this argument? Is it to serve the community or to elevate myself? Is it born of pain transformed into responsibility, or resentment weaponized as righteousness? The Netziv of Volozhin (HaEmek Davar on Numbers 16:1) reads Korach’s actions as the sin of undermining national unity under the guise of religious idealism—proof that good language can be marshaled for bad ends.

But even noble motive and respectful argument are not enough. There is a third element: relationship. In Tosefta Yevamot 1:10, we’re told that despite their halakhic disagreements, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai continued to marry into each other’s families. Ein zeh sinat chinam—this is not baseless hatred. This is machloket as covenantal love: disagreement held within a shared destiny.

Korach, by contrast, stages his revolt as rupture. There is no attempt to engage Moses privately, no shared project, no loyalty to the collective. It is, as Rav Soloveitchik might say, a rebellion of the ego rather than a crisis of faith. Once communal bonds are severed, even the language of Torah can become an instrument of destruction.

Rav Kook offers a powerful counter-model. In Orot HaKodesh, he writes:

"The multiplicity of opinions in Israel is not a weakness but a strength. Each soul sees a different facet of divine truth. Peace will not come through erasing differences, but through their elevation.” Arguing l’shem shamayim means arguing with a sense that the other side is not just tolerated, but needed. That truth is too large to be captured by any single voice.

This has deep resonance in our time. Whether in debates over Israel and Zionism, over inclusion in Jewish spaces, over halakha and innovation, or over the soul of American Jewish identity—conflict is inevitable. The challenge is not to eliminate machloket, but to redeem it. To ensure that our arguments do not imitate Korach, even when they claim his slogans.

Levinas famously wrote that “truth arises from the face of the other.” To see the face in an argument is to remember that disagreement is not war. That even passionate dissent must preserve the humanity of the other side. Korach’s failure was not merely theological—it was interpersonal. He erased the face. He turned community into competition.

The Torah vindicates Moses and Aaron not only with fire, but with blossoms. Aharon’s staff is placed in the Tent of Meeting and overnight it sprouts blossoms and almonds (Numbers 17:23). Not by might, nor by power, but by fruit. A quiet flowering of legitimacy. A reminder that real leadership, like real argument, grows—not explodes.

So how should we argue?

With humility, like Hillel.

With integrity, like the sages who preserved dissent.

With relationship, like those who disagreed but still broke bread.

With awareness of the face across from us.

And with a longing not for victory, but for understanding.

May we be disciples of sacred argument.

May our debates strengthen rather than shatter.

May we learn to disagree like Hillel and Shammai—l’shem shamayim.

And may our arguments lead us not into the pit of Korach, but into a blossoming of truth, humility, and peace.

Shabbat Shalom.